This is the second part of my series about Speedhacking. Last week I looked at the reasons why you should participate, now I'm going to give some tips for beginners.

Are you going to join a speedhack, or other type of game jam, for the first time? Here are some tips!

How to limit your scope

In my previous post, I wrote about how important it is to limit your scope. But how exactly do you do that?

If you're really a beginner, keep it very simple. If you think an idea might be just doable, cut it in half. Make your own variant of Snake. Pacman. Tetris. These are the type of games that are feasible in a weekend.

Don't invent everything new, but remake a game you already know. Is it bad to make a clone? Of course not, remaking famous old games is excellent practice. You won't expect a beginning chef to create delicious new recipes - first they have to master the classic ones. Start with a remake, and if you find some extra time, you can always add your own flavour and twists to it.

It's best to choose from the genres of arcade games or puzzle games. Arcade games are focused on reaction speed, and usually have just a single screen or a single mechanic that is repeated over and over again, with increasing difficulty. This provides an interesting challenge without requiring you to design lots of extra "content".

By "content" in mean levels, graphics, storylines. Any genre that requires a lot of that is really tough to pull off in just 72 hours. Examples of these are platformers or RPGs. You may think that it should be possible to program a character like Super Mario in just a weekend. And you would be correct. The problem is that what makes Super Mario fun, are the levels. Designing levels takes time. And the amount of time you spend designing is directly proportional to how fun your entry will be. There is no way to speed up the process. And it eats away from your polishing time.

Schedule polishing time

It's possible (although not very healthy) to spend a good 40 hours out of those 72 hours making games - that's an entire work week compressed in 3 days! But working to the limit is a sign that you set the bar to high. With a lower bar and fewer hours of work, you can actually achieve better results.

I've seen it happen that participants could only work on their entry for one day instead of the weekend, for reasons (work, life, illness, whatever). And still ended up with a high-ranking little arcade game.

It's usually not the case that you need a fantastic new idea to make a game work. Instead, what makes a game work is a decent idea with a lot of polish. Making a game fun means polishing it. The amount of time you set aside for polish determines the success.

What is meant by polish? Playtesting. Balancing the game. Take some time to actually play the game yourself. Let somebody else try it. Is it too difficult? Is it too hard? Is the goal of the game intuitive? Add finishing touches. Sound effects and music usually come in last but add a lot to the fun factor.

So instead of planning a game that takes 40 hours to implement, plan for a game that takes 20 hours to implement, then spend any remaining time adding as much polish as you can. The good thing is that usually, this is the most fun aspect of game development. In this phase, every tweak, every added line of code immediately improves your game in a visible way.

How to use the rules to your advantage

It's easy to see the random rules as annoying barriers that stand in the way of the game you really wanted to make. For example, maybe you have decided that you wanted to remake Sim City. Then the rules are announced, and maybe one of the rules is that the theme must be "Gravity". What do I do with gravity? How on earth do I combine Sim City with gravity? The trick is not to get too hung up on a single plan. Be opportunistic, not dogmatic. Keep your options open. Be willing to make any of a range of games - arcade games, puzzle games, etc. So maybe you can't make Sim City. Is that really the only possible game you could ever make?

Another way to look at it is this: Don't see the rules as limitations, but as stepping stones for your imagination. This is an opportunity to think out of the box. It would be so cool to play Sim City on the flying rocks of Pandoran!

I can't do art

Worried you can't do good art? Again, what may appear as a limitation is really a stepping stone for your imagination. Focus on what you do know. Make a game that is focused around patterns of geometric shapes - like for example Circles. Even better, just use only text. There are some really cool games made with just text, like Dwarf Fortress and Nethack.

Make a word puzzle game, or a text adventure. Focus on procedurally generated art. Or use a super-low resolution (but scale it up for modern screens). It's much easier to generate a lot of art if sprites are only 8x8 pixels.

I'm not a good programmer

Worried that you're not a good enough programmer? Well, the bad news is, you do need to know some basic programming. Actually, you need a combination of skills to make a good Speedhack game, but programming stands at the basis.

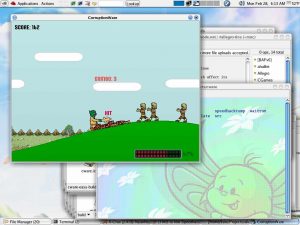

But then again, it's just a matter of matching the scope with your skills. As long as you're willing to learn, you can start really small. Can you write "Simon Says"? Can you write "Hang man"? Can you write "Higher, Lower"? These games can be programmed in Scratch! (Unfortunately I haven't seen Allegro bindings for scratch yet, so that would make them inadmissible to TINS. But you get the point). Combined with the right art, design and sound, you can still make something cool. Perhaps you're not going to win the competition with these games, but the challenge is purely your own: can you become a better programmer?

Teaming up

Another way around a skill gap is to team up with somebody else. Some competitions, including TINS, allow this. Is it really possible to let teams compete against individuals? How can that be a fair competition? Certainly I've seen some very good TINS entries in the past that were made by teams. But don't underestimate the extra difficulties involved in teaming up. There won't be enough time to do all the meetings and huddles that usually involve joint programming efforts. You need to be able to rely on each other, and find ways to remove interdependencies so that you're not constantly waiting on each other.

I'm not saying you shouldn't join a team. Just be aware of the complications. Teaming up may help you to work around a skills you lack, but requires all of you to have communication skills in abundance.

Here's that promo bit again

So, did I convince you that it's feasible? Do you think you can do it?

Why not give it a try? The next TINS competition will be held from October 20 to 23. Head over to tins.amarillion.org, register and sign up!